Callum Quinn, © 2019

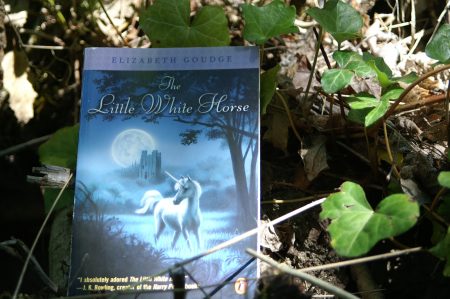

The Little White Horse

By Elizabeth Goudge

The (a) story is about thirteen-year-old Maria Merryweather, who is sent to live in Moonacre Manor in the village of Silverydew with her second cousin (the summary of my copy says ‘uncle,’ but the book itself specifies ‘second cousin,’ so I’m going with that) and nearest living relative, Sir Benjamin. She is joined by her governess, Miss Heliotrope, and her dog, lovingly named Wiggins.

At first, things at Moonacre seem perfect. Her original fears of coming to the country are washed away by the beauty of the landscape and the friendliness of the people. Sir Benjamin is warm and welcoming and takes her horseback riding in the early mornings. Even her childhood friend Robin has re-entered her life, along with his beautiful mother, who treats Maria like one of her own.

But beneath the surface, there is trouble in Silverydew. A centuries-old feud has split the citizens in half. The Men from the Dark Woods poach on Sir Benjamin’s property and steal livestock from the villagers. Wrongs committed by past Merryweathers need to be put right, and Maria may be just the person to do it.

The (A) story is about balance. This is demonstrated most clearly through the dynamics of the “Sun” and “Moon” Merryweathers, who are said to be most compatible with each other, and yet, historically, also seem to constantly butt heads. The Merryweather emblems are a lion (for the sun/bravery) and a unicorn (the moon/spirit); the family motto above the mantel reads: “The brave soul and the pure spirit shall with a merry and a loving heart inherit the kingdom together,” and this union is precisely what it takes in the end to rid Silverydew and Moonacre of their demons.

This theme can also be observed by the trade (or lack thereof) war that is taking place between the Men from the Dark Woods and the rest of Silverydew. The Men keep all the wild game and fishing from the villagers while the villagers keep ownership of all the livestock. Instead of building up a trade together, and furthermore, a balance between the two, the Men take it upon themselves to steal from the villagers, and the villagers settle for a life without fresh fish. Obviously this has created and imbalance and further problems within the community.

Furthermore, the idea of balance tends to be demonstrated through masculine and feminine powers, as all the Moon Merryweathers of this story are women, and any representations of the Sun are male.

I cannot remember how old I was when I first read this story, but I know it’s been many years since I last picked it up. And what I’d remembered until now had been only vague images and a few key characters.

After reading it as an adult, there are some things that strike me as… well…“icky.” Let’s take some time to point out that this book was first published in the forties, and takes place exactly a century earlier than that, and it’s safe to say that some of the finer details are difficult to swallow by today’s standards. For instance, the whole male/female balancing act is centered on traditional stereotypes: men couldn’t possibly be artistic and sensitive, and women are always troublesome and ask too many questions. One character (of course, it’s a parson, so this isn’t too surprising) even tells our heroine that “excessive female curiosity is not to be commended… Nip it in the bud, my dear, while there is time.”

Ugh.

Also, the men of Moonacre Manor tend to dislike females. Granted, much of this dislike seems to stem from the original problems and disagreements between Sun and Moon Merryweathers, but frankly, reading this book as a feminist, I got very tired very quickly of the male characters having no patience for women who ask questions or wish to satisfy curiosity, all the while implying that any woman they happen to end up liking must be some kind of “exception” to the rule. You could argue that all of this is redeemed by the ending, and the establishment of balance, but that doesn’t make it any easier to sit through on the way.

Also, typical of high class families of that time, there is a lot of cousin-marrying taking place, and in one instance the couple met when she was ten and he was twenty-five.

Ick.

They explain that they became engaged once she “grew up,” but while my mind was screaming, Please tell me that at least means eighteen!, at the end of the book our own heroine gets married when she’s no more than fourteen or fifteen, so I feel there’s not much chance of that.

But apart from the ick factor I also had trouble with the suspension of disbelief through various sections of the book. Firstly, the story seems based in magical realism, but the “magic” aspect of it is very background. Not to say that this makes the story bad—not in the least. It’s very reminiscent of traditional fairytales, and a lot of it is beautifully done.

However, for some reason I just wasn’t buying a lot of it. As an example, Maria’s childhood friend Robin used to “visit” her when she was in London. It could be very possible that he used to live in London, too, but instead it is explained that he was able to visit her while he was dreaming. Not much more explanation than this is given, except that everyone consists of a body and a spirit, and sometimes the spirit is able to leave the body and just wander around during sleep.

This is an interesting concept, if only the author went more in depth with it. In the entire story, Robin seems to be the only character with this ability, and it is barely mentioned again afterward.

Also, like in most fairytales, the animals have human qualities; they don’t talk, but they can clearly communicate and don’t act much like animals. The cat, for instance, can write in hieroglyphics in the ashes of the fireplace. The “dog,” Wrolf (which is, in fact, a lion), doesn’t eat any of the people or the other animals for starters, and seems to live to protect the Merryweather family.

Sure, there are dwarves and unicorns and fairy-like people dotted throughout the town, but the main plot appears very non-magical (also, it could possibly be argued that the word “dwarf” in this context is the non-PC term for a little person). So overall, whenever something slightly less than normal occurs, my mind has trouble grasping it in this world.

As well as that, for any non-religious readers the book can seem a little preachy at times. On occasion, the author will throw in a hymn or a song that doesn’t really seem necessary to the plot, or to anything really, other than an excuse for the author to show off her lyrical skills.

Originally, I found myself really struggling to grasp at the (A) story. The theme of balance does seem to fit from my perspective, but there are plenty of times when the messages also seem contradictory. Like the fact that there is such a low opinion of women among the male characters, yet they are all dependent on Maria to solve their problems. Over the course of the story there’s this underlying sense from the townspeople that leads her to believe they are expecting something of her; in the end, she has to go into the Dark Woods and come face-to-face with the thieves and poachers that live there.

Now, what does it take for a young girl to go up against a group of black-hearted men who live in the middle of a forbidden forest? Maybe some sense of adventure? Curiosity? A questioning and somewhat “rebellious” personality? All the things that the same men with the same expectations of her are saying it’s “bad” for a “female” to have?

Is the book worth a read? I don’t think it’s easy to find a book I wouldn’t recommend. Like I mentioned above, parts of it are beautifully written. And it is very reminiscent of a classic fairytale, even making an argument over pink geraniums actually seem logical. The whole dynamics of the Sun and Moon, lion and unicorn, and the importance of the union are very powerful metaphors. And, despite the woman-hating, the characters are, for the most part, charming and likeable.

I’d say if you’re in the mood for a good fairytale, go ahead and pick up The Little White Horse. Just don’t expect its messages to always be relevant to a modern audience.